Category Archives: Reference and Research

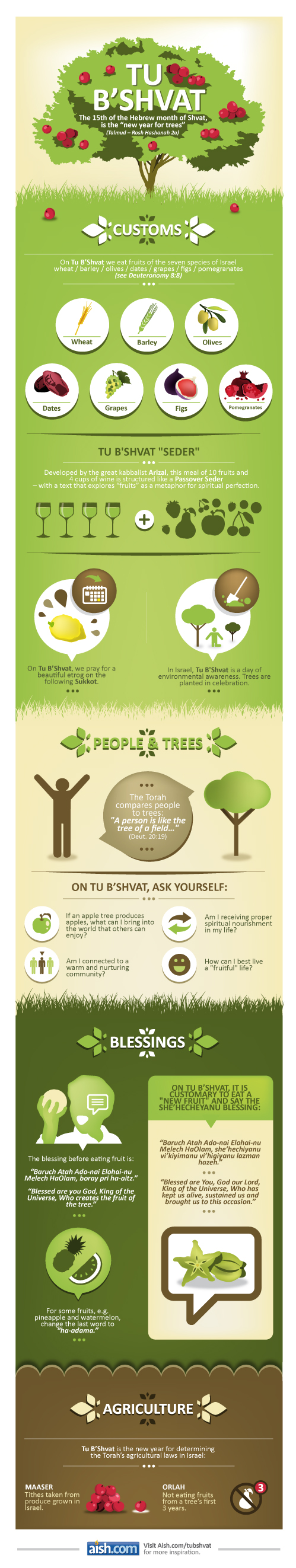

Counting the Omer

Counting of the Omer is a verbal counting of each of the forty-nine days betweenthe holidays of Passover and Shavuot. This practice derives from the Torah commandment to count forty-nine days beginning the from the day on which the Omer, a sacrifice containing an omer-measure of barley, was offered in the Temple in Jerusalem, up until the day before an offering of wheat was brought to the Temple on Shavuot. The Counting of the Omer begins on the second day of Passover, and ends the day before the holiday of Shavuot, the ‘fiftieth day.’

The Amidah ~ Shemoneh Esrei

How Jews Wake-Up: Modeh Ani

The first instruction in the Code of Jewish Law is: “Be strong as a lion when you wake-up in the morning to serve your Creator.” Here is the blessing on waking-up, to be said before you get out of bed:

Hebrew:

.מודה אני לפניך מלך חי וקיים, שהחזרת בי נשמתי בחמלה; רבה אמונתך

Transliteration:

Modeh Ani L’fanecha

Melech Chai V’kayam

Shehechezarta Bi Nishmati B’chemla

Raba Emunatecha

Translation:

I offer thanks to You,

Eternal One,

for lovingly restoring my soul to me;

Your faithfulness is great.

* the first word of the blessing is gender-specific: modeh for a man, modah for a woman.

Tallit and Tefillin How-To Guide

Key Jewish Sacred Texts

Tanakh: the acronym referring to the Torah, the Nevi’im and the Kethuvim.

Torah: the first five books of the Bible. Also referred to as the Pentateuch or The Five Books of Moses – Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, and Deuteronomy. Each book is broken into 10-12 weekly parshiyot (54 in total).

Nevi’im: the second part of the Bible, comprised of the eight books of Prophets and the Twelve Minor Prophets (so-called because they are shorter texts): Joshua, Judges, Samuel, Kings, Isaiah, Jeremiah, Ezekiel, The Twelve (Hosea, Joel, Amos, Obadiah, Jonah, Micah, Nahum, Habakkuk, Zephaniah, Haggai, Zechariah, Malachi).

Kethuvim: the “writings,” divided into three main parts:

1. Psalms, Proverbs, Job

2. Song of Songs, Ruth, Lamentations, Ecclesiastes, Esther (also referred to as Hamesh Megillot, the five scrolls)

3. Daniel, Ezra-Nehemiah, Chronicles (historical texts)

The Septuagint (LXX): the name commonly given to the Koine Greek translation of the Jewish scriptures, translated in stages between the 3rd to 1st century BCE in Alexandria, Egypt. In the Septuagint, the Torah and Nevi’im are established as canonical, but the Kethuvim appear not to have been definitively canonized yet.

Mishnah: literally defined as oral instruction, the Mishnah is a compilation of the written records of oral discussions of various laws completed in 200 CE. Believed to be compiled in its final form by Rabbi Judah al-Nasi, “Rabbi.” Divided into six orders, each with numerous subsections called tractates: Zera’im (seeds), rules about agriculture; Mo’ed (appointed times), rules about Sabbaths and festivals; Nashim (women), primarily marriage laws; Nezikin (damages), rules about money and legal disputes; Kodoshim (holy things), Temple procedures; Teharot (purities), ritual impurities and purification.

Tosefta: literally “addition.” Further rabbinic comments on most of the topics covered in the Mishnah.

Talmud: exists in two forms – the Jerusalem Talmud (abbreviated y.) and the Babylonian Talmud (abbreviated b.). Compiled during the 3rd to 6th centuries, the Talmud consists of extracts from the Mishnah, accompanied by commentary called Gemara (learning). Represents the body of Jewish civil and ceremonial law.

Midrash Rabbah (Great Midrash): collection of rabbinic comments on biblical text, completed in 1545. Contains 10 midrashim: the five books of the Torah and the Five Scrolls (Song of Songs, Ruth, Lamentations, Ecclesiastes, Esther). Individual sections are referred to by their biblical title (i.e. Genesis/Bereshit Rabbah, etc).

Halakhah and Aggadah: descriptive types of rabbinic comment. Halakhah is legal comment, referring to “the way” of the Torah, concerned with explicating, applying and making sense of the legal materials in the Bible. Aggadah is non-legal comment, a more amorphous category, including theology, legend, sayings, prayer and praise.

Sefer ha-Zohar: The Book of Splenour, the central text of Kabbalah, the mystical branch of Judaism.

Responsa: thousands of volumes of answers to specific questions on Jewish law. If the Talmud is a law book, then the responsa are case law.

How to Havdalah

Family Shabbat: Checklist and Timeline

Oh, how I envy those who have celebrated Shabbat as part of their lives since childhood. For them, the routine and ritual of the event seems to come naturally: they were there to help set the Shabbat table, listen to their parents and grandparents recite the blessings, sing songs that are now etched in their memories, and read Torah at Saturday services with friends and neighbours. I envy the innate comfort they have with the holiday, the effortlessness with which they participate, the sense of security and connectedness that its practice brings. As a Jew-in-the-making, I have had to learn the Shabbat rituals and obligations, sifting through religious texts, rabbinic instruction, historical overviews, how-to-guides, and directives from well-meaning columnists, bloggers, and friends. As a Reform Jew, I have then had to critically examine these obligations and their meaning within the context of my personal circumstances. As the Central Conference of American Rabbis (CCAR) stated in the Centenary Perspective of 2004, “within each area of Jewish observance Reform Jews are called upon to confront the claims of Jewish tradition, however differently perceived, and to exercise their individual autonomy, choosing and creating on the basis of commitment and knowledge.” In what follows, I have outlined the Shabbat I have created with my family, informed by the mitzvot of remembering Shabbat and keeping it holy.

Continue reading Family Shabbat: Checklist and Timeline

Weekly Torah Readings

The Torah is divided into 54 sections called parshiyot and one parshah (singular) is read each week throughout the year (two occasionally). Reading the weekly Torah portion is a hallmark of the learned Jew as new insights emerge each time one engages in the pursuit of Torah. The cyclical nature of the parshiyot reflects Judaism’s connection to time and season. In the synagogue service, the weekly parshah is followed by a passage from the prophets, which is referred to as a haftarah (haftarot, plural). Contrary to common misconception, “haftarah” does not mean “half-Torah.” The word comes from the Hebrew root Fei-Teit-Reish and means “concluding portion”. Usually, the haftarah portion is no longer than one chapter, and has some relation to the Torah portion of the week.

The Torah and haftarah readings are performed with great ceremony: the Torah is paraded around the room before it is brought to rest on the bimah (podium). The reading is divided up into portions, and various members of the congregation have the honor of reciting a blessing over a portion of the reading. This honor is referred to as an aliyah (aliyot, plural; literally, ascension).

To access the most comprehensive, non-denominational weekly Torah and Haftarah portion go to Hebrew Calendar: http://www.hebcal.com/sedrot/. Below is a table of the weekly parshiyot in the order in which they are read:

The Taryag Mitzvot: 613 Commandments

In Judaism, there is a tradition that the Torah contains 613 mitzvot (Hebrew for “commandments,” from mitzvah – מצוה — “precept”, plural: mitzvot; from צוה, tzavah- “command”). According to tradition, of these 613 commandments, 248 are mitzvot aseh (“positive commandments” commands to perform certain actions) and 365 are mitzvot lo taaseh (“negative commandments” commands to abstain from certain actions). Three-hundred and sixty-five corresponded to the number of days in a year and 248 was believed by ancient Hebrews to be the number of bones and significant organs in the human body. Three of the negative commandments can involve yehareg ve’al ya’avor, meaning ‘One should let himself be killed rather than violate this negative commandment’, and they are murder, idol worship, and forbidden relations.

The Talmudic source is not without dissent concerning the number of mitzvot, however. Some held that this count was not an authentic tradition, or that it was not logically possible to come up with a systematic count. This is possibly why no early work of Jewish law or Biblical commentary depended on this system, and no early systems of Jewish principles of faith made acceptance of this Aggadah (non-legal Talmudic statement) normative. The classical Biblical commentator and grammarian Rabbi Abraham ibn Ezra denied that this was an authentic rabbinic tradition. Ibn Ezra writes “Some sages enumerate 613 mitzvot in many diverse ways […] but in truth there is no end to the number of mitzvot […] and if we were to count only the root principles […] the number of mitzvot would not reach 613” (Yesod Mora, Chapter 2).

Whether dictated by tradition or Torah, Maimonides (RaMBaM), in his Sefer HaMitzvot, arranged the 613 Mitzvot in groups; the Positive Mitzvot into ten groups and the Negative Mitzvot into ten groups.

Continue reading The Taryag Mitzvot: 613 Commandments

Glossary of Key Halachic Terms

The term Halacha refers to the collective body of Jewish religious law, including biblical law and later talmudic and rabbinic law, as well as customs and traditions. Halacha guides not only religious practices and beliefs, but numerous aspects of day-to-day life. Although Halacha is often translated as “Jewish Law”, a more literal translation might be “the path” or “the way of walking.” The word derives from the root that means to go or to walk.

When discussing Halacha and the practices and rituals that characterise a Jewish life, numerous terms are used that are often unfamiliar to the uninitiated. I have listed some of them below. Many, as you will see, are related to the rules of taharat hamishpacha, an area of Jewish law that relates to women, marriage and sexuality. For more information concerning these subjects, here is an excellent resource available online: Nishmat Yoatzot Halacha.

Balanit – Mikveh attendant

Bediavad – Refers to a less than optimal manner of fulfilling a halachic requirement, acceptable after the fact or in difficult situations (opposite of l’chat’chila)

What Judaism Offers

WHAT JUDAISM OFFERS FOR YOU: A Reform Perspective

by David Belin

Albert Einstein once said that he was sorry to be born a Jew because he was thus denied the opportunity and personal satisfaction of independently choosing Judaism. Today, in our free and open society, Judaism is in a sense a matter of choice for everyone-both those who have been born Jews as well as those individuals who have not been raised in the Jewish tradition. Each year thousands enter the Jewish community through study and a formal ceremony known as conversion.

No booklet-indeed, no book-can fully explain all that Judaism offers to help individuals reach their full potential and become happier and more fulfilled human beings. But for those who desire a brief glimpse into the wonders of Judaism-born Jews, Jews by choice, non-Jews who are interdating or have married Jews, children of intermarried families, and people who have no direct contact with the Jewish community but seek to explore it-this booklet gives a brief introduction to Judaism from a modern Reform Jewish perspective. If what you read appeals to you, hopefully you will want to enlarge your understanding and learn more about how special, how unique, Judaism is-how Judaism can help people best fulfill their hopes, dreams and aspirations-how being part of the wonderful heritage, culture, and religious philosophy of Judaism can make life more meaningful for you and for those you love.