Dvar Tzedek

By Jonathon Soffer

Now that the Exodus narrative is over, the gripping accounts of our ancestors that pervaded the first two books of the Torah fade into distant memory and we begin reading the detailed guidelines for the construction and use of the Mishkan, the Tabernacle. While initially many of these details seem extraneous or irrelevant, they contain within them deep wisdom and insight into our lives and moral obligations as Jews.

The korban tamid, the continual offering, described in Parashat Tetzaveh, is a compelling example of the deep symbolic meaning that can be found in the details of ritual. Before the episode of the Golden Calf, God gives the commandment to offer the tamid: “Now this is what you shall offer upon the altar—two yearling lambs each day, regularly. […] It shall be a continual burnt-offering throughout your generations at the door of the tent of meeting before God, where I will meet with you, to speak there to you.”

On the surface, it appears that the korban tamid was a simple, perfunctory sacrifice, offered twice daily. Several commentators, however, suggest that the ritual contains important spiritual lessons. The Abarbanel, a 15th-century Portuguese Torah scholar, explains that we offer the tamid twice daily to correspond to the dual physical and spiritual freedoms which God provided by freeing us from slavery in Egypt, and engaging us in an eternal covenant at the revelation at Sinai.

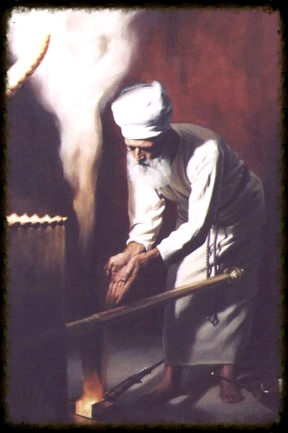

The Maharal, Rabbi Judah Loew ben Bezalel, a prominent 16th-century mystic and Torah scholar, brings a remarkable anecdote in the introduction to his ethical work, the Netivot Olam, which looks at the tamid from another perspective:

In this text, the Rabbis are debating which is the most fundamental sentence in the Torah. The first two suggestions—the Shma and the ‘love one’s neighbor’—are predictable and appropriate possibilities. The third option, “and the one lamb you shall make in the morning,” refers to thekorban tamid. This seems strange. What is the allure of this passuk that it could be the most important sentence in the Torah?

The Maharal, in elaborating on this ostensibly bizarre choice, suggests that this quote speaks to the need for consistent commitment and constant engagement in Jewish life. The korban tamid is so important because, as a sacrifice conducted every single day, it symbolizes our unwavering commitment to living a life replete with Yiddishkeit, without which other commandments become meaningless or irrelevant.

According to this perspective, a living Judaism cannot be limited to sporadic rites or cultural practice; it must be something that infuses our daily lives. Though not everyone’s Judaism needs to be identical (indeed, one of the glories of Judaism is the divergence of our expressions), any expression of Judaism should be perpetual. We need our tamid—an involvement that, in its own way, is shown daily.

While this message is personally relevant to me in the realm of traditional ritual observance, I believe that it issues a call in the realm of ethical mitzvot, as well. The Torah commands us to help people in need, to protect the widow and the defenseless and to empower the most marginalized. The tamid reminds us that these actions cannot be intermittent initiatives, but must instead be persistent features of our Jewish lives and identity. Every day we must strive to perfect this world, in the kingdom of Shadai [God].

The challenge is to find the constant inspiration and motivation to foster perpetual involvement. In the absence of the daily korban tamid, what can remind and encourage us to achieve a constant and consistent commitment to the ethical obligations of Judaism? Parashat Tetzaveh begins with another “tamid” (constant) which can serve in this role. The ner tamid, the eternal light, which still shines above the Holy Ark in our synagogues today, is a reliable reminder of our Ultimate responsibilities. In particular, this visual symbol can help us remember our responsibilities to respond to injustices in the developing world, which are sadly so often “out of sight, out of mind.” As we read the holy words of this parashah, it is our task to find our tamid—the eternal reminder of our Eternal calling.

Soffer, Jonathan. "Dvar Tzedek." American Jewish World Service. (Viewed on February 8, 2014). http://ajws.org/what_we_do/education/publications/dvar_tzedek/5774/tetzaveh.html

Tetzaveh 5774

By Joanna Bruce

At the end of this week’s portion, following the many intricate descriptions of the priests’ clothing and the even more specialised garments of the High Priest, we are led on an interesting detour into an account of the altar for the burning of incense.

1) You shall make an altar for bringing incense up in smoke; … 6) And you shall place it in front of the dividing curtain, which is upon the Ark of Testimony, in front of the ark cover, which is upon the testimony, where I will arrange to meet with you. (Exodus 30:1, 6)

This section seems out of place. It would make far more sense for this account to be placed when all the other artifacts used in the Temple service were described in last week’s portion. Why is the incense altar described here completely out of context?

The items described last week such as the Ark, Menorah, Table etc. seem to have a unity of purpose, one way or another they are all about revealing God and strengthening our connection to Him.

God commands Moses to ‘make me a house so I may dwell in it’ (Exodus 25:8) and the Menorah and the Table can be understood at its furniture, the offerings given on the altar are our house warming gifts. Is the incense offering so different? Is it not the potpourri or the smell of fresh coffee or baking bread? The smells that make us feel at home.

The fact that it has been placed in a separate section of the Torah would indicate that its function was connected with the Temple but has a different purpose from the other holy objects.

The function of the sacrifices in the Temple was as a vehicle for communication between the people and God. The people would ‘offer’ something of themselves either as a collective, in the form of a daily offerings, or as individuals when bringing a sin offering. This was our conversation with God, “I’m sorry”; “Thank you”, “Please help” and God’s reply was in the miraculous acceptance of the sacrifice.

The incense has a very different purpose. The incense was offered to God at the very heart of the Temple, right in front of the Holy of Holies where the Ark was kept. On Yom Kippur the ceremony went literally one step further and was given in the Holy of Holies itself. The incense would create a cloud of smoke that obscured the curtain and on Yom Kippur would fill the Holy of Holies.

Its purpose was to conceal rather than reveal, to create a distance between God and humanity rather than connection. It is the diametric opposite to all those other objects and ceremonies in the Temple and it is for this reason that it is described in a different place.

Concealment seems to be a necessary component of our relationship with God. There is an element of the Unknown and the Unknowable about God that is important and fundamental. The uncertainty that concealment creates is the basis of our capacity of free choice, when we choose to know and follow God we are overcoming the doubts we have because things are not perfectly clear. But our commitment is all the greater because we had to overcome that challenge.

Bruce, Joanna. "Tetzaveh 5774." Limmud. (Viewed on February 8, 2014). http://limmud.org/publications/limmudononeleg/5774/tetzaveh/