Link to Parsha: http://www.hebcal.com/sedrot/pinchas

Torah: Touched By God

By Rabbi Tony Bayfield

God spoke to Moses saying: Pinchas, son of Eleazar son of Aaron the Priest, has turned back My anger from the Israelites by displaying among them his zeal for Me, so that I did not wipe out the Israelite people in My zeal. Say, therefore, ‘I grant him my pact of friendship. It shall be for him and his descendants after him a pact of priesthood for all time, because he was zealous for his God, thus making expiation for the Israelites.’ (Num. 25:10–13)

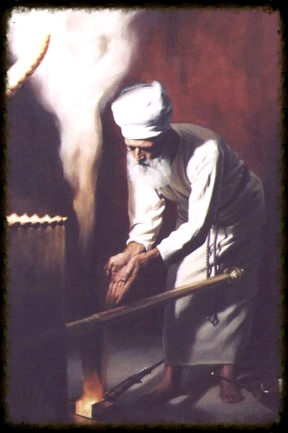

I stand up in honour of the Torah, follow it round the synagogue out of respect with my eyes and my posture. But not as a sacred totem, nor as a manifesto carefully crafted for ease of maximum buy-in. What tells me that this is a document touched by God is its elusive character, its deceptive complexity and the depth of challenge it throws down. Like God, it will not be possessed or summoned to yield simple truths. It does not provide an incontrovertible programme with which to capture the souls of others. Rather, it bothers, provokes, disturbs. Sometimes even ‘touched by God’ will not do. There are dark passages and characters in the Torah, passages displaying zealotry and applauding violence. By men.

Pinchas.

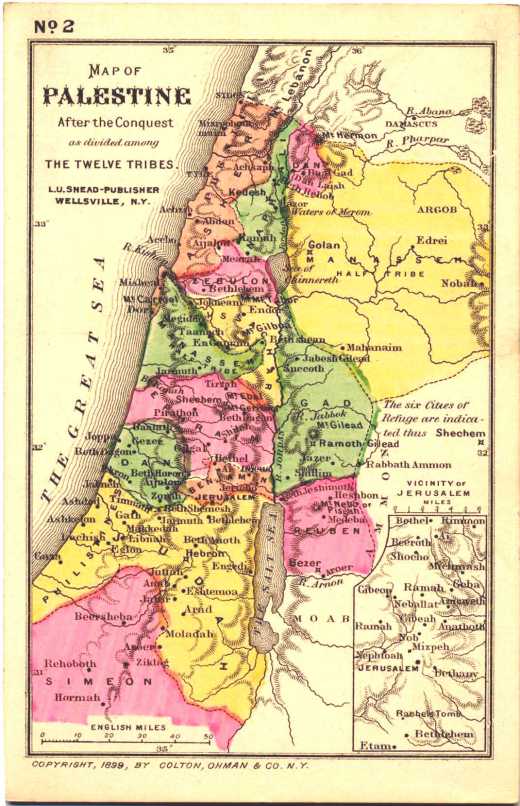

We are near both the end of the Book of Numbers and the Promised Land – in fact, at a place called Shittim (which means ‘acacia trees’). The sons of Israel have become involved with women from the locality and have embraced them in immoral and idolatrous practices. A plague is raging. Just as Moses is about to deal with the situation, a man called Pinchas (Phinehas), grandson of Aaron and son of Aaron’s son Eliezer, grabs hold of a spear, rushes into a private chamber, finds an Israelite man called Zimri having sex with a Midianite woman called Cozbi and despatches them both through the stomach. The plague is checked, the defection is halted and God rewards Pinchas with the pact of hereditary priesthood. That is the story.

By and large, the traditional Jewish sources are accepting and approving of Pinchas’ act of zealotry. The end amply justifies the means. How could that not be so, since the text of the Torah itself explicitly endorses Pinchas’ act? Yet hereditary priesthood is high reward indeed for the work of an impulsive, murderous moment. Characteristically male.

I remember, in my student days at the Leo Baeck College in London, being introduced to a particular midrashic sequence from a collection known as Midrash Tanhuma in which both the ancient authors and my teacher, Professor Raphael Loewe MC, revelled in the details – of where precisely the spear had entered and exited and of the exact position that Zimri and Cozbi had adopted at the moment they were caught in flagrante delicto. This midrash turns Pinchas into something of a strong man and has him running round the camp with the unfortunate couple impaled on his spear like an exotic kebab.

Pinchas turns up in later midrashic history in all manner of positive places – at the head of the Israelites in their campaign against Midian, intent on completing the good work he himself had begun by slaying Cozbi (Num. R. 22:4.); avenging his maternal grandfather Joseph, who had been sold into slavery by the Midianites (Sifrei Num. 157; B.T. Sot 43a.); miraculously slaying Balaam (B.T. Sanh. 106b.); as one of the two spies sent by Joshua to Jericho (Targum Yerushalmi Num. 21.22.), where he managed to make himself invisible like an angel (presumably he could be trusted to enter Jericho without having recourse to the services of its best-known inhabitant).

The Mishnah goes so far as to codify the incident: ‘If a man …. cohabits with a gentile woman, he may be struck down by zealots’ (M. Sanhedrin 9:6.) and a midrash has Pinchas recalling this halakhah (law) as legal justification for his own behaviour (Sifrei Num. 131.) – even without Moses’ permission, a Moses paralysed by his own marriage to a Midianite woman (Exod. 2:16–21; B.T. Sanh. 82a; Num. R. 20:24).

But what I find truly fascinating, terrifyingly fascinating, is the way that the story is dealt with in contemporary Jewish Bible commentary. I want to quote at some length from Gunther Plaut, that renowned rabbi and scholar from Canada, whose major commentary appeared in 1981.

Plaut raises the moral question of how a priceless reward could be given for an act of killing and says: “ By post-biblical and especially contemporary standards, the deed and its rewards appear to have an unwarranted relationship. But the story is biblical and must be appreciated in its own context. To begin with, Phinehas is rewarded not so much for slaying the transgressors as for saving his people from God’s destructive wrath. But, even if we assume that the text concentrates on the former merit, we must remember that the Moabite fertility cult was, to the Israelites, the incarnation of evil and the mortal enemy of their religion.” He then goes on to quote George E Mendenhall, who identifies the plague with bubonic plague and suggests that Zimri was following a pagan precedent for dealing with the affliction (it is remarkable what one used to be able to get in public health benefits!). Plaut, however, concludes: “ Phinehas did not act out of superior medical knowledge. He saw in Zimri’s act an open breach of the Covenant, a flagrant return to the practices that the compact at Sinai had foresworn … This was the first incident in which God’s power over life and death (in a juridical sense) passed to the people. Phinehas’ impulsive deed was not merely a kind of battlefield execution but reflected his apprehension that the demands of God needed human realisation and acquired a memorable and dramatic example against permissiveness in the religious realm.”

There are some voices from the classical period which sound much more disturbed by Pinchas than Plaut appears to be. A passage in Tractate Sanhedrin (82a) struggles with the legal problems. Why no warning? Why no evidence? Why no trial? The answer that emerges is that the act was licit only because the couple were caught in flagrante delicto. Had they finished fornicating, then Pinchas’ zealotry would have been murder. If Zimri had turned on Pinchas and killed him first, he would not have been liable to the death penalty, since Pinchas was a pursuer seeking to take his life. Even here the rabbinic anxiety is more convincing than the conclusions at which they arrive to allay it. The question was taken up again in the nineteenth century by Samson Raphael Hirsch, who offers the same lame explanation: “Phinehas acted meritoriously only because he punished the transgression in flagrante delicto, in the act. Had he done it afterwards it would have been murder.”

That same passage from Tractate Sanhedrin also reports Rabbi Hisda as stating explicitly that anyone consulting ‘us’ about how to act in a similar situation would not be instructed to emulate Phinehas’ example. Interestingly, a connection is made between Pinchas’ slaying of Zimri and Cozbi and Moses’ slaying of the Egyptian overseer. Because the Exodus text offers little comment and refrains from explicit praise of Moses, the rabbis felt more able to voice doubts here. Some even connect Moses’ act of killing with the punishment of not being allowed to enter the Promised Land. But they are still a minority.

I want, at this point, to go back to the passage that I quoted from Gunther Plaut. “This was the first incident in which God’s power over life and death (in a juridical sense) passed to the people.” I have severe doubts about God’s power over life and death being taken up by religious traditions and religious authorities and those four words ‘in a juridical sense’ only increase my discomfort. For there is no juridical context to Pinchas’ act. He acted alone; as the text implies and tradition makes explicit (Jerusalem Talmud 25,13.), without the approval of Moses or the religious, political and legal authorities of his time; no warning was given, no evidence adduced, no trial took place. As Plaut says: “ His act reflected his apprehension that the demands of God needed human realisation and required a memorable and dramatic example against permissiveness in the religious realm.” In this, Plaut is absolutely at one with an early twentieth-century, Orthodox commentator, Baruch Epstein, author of Torah Temimah. According to Epstein there is justification if such a deed is ‘animated by a genuine, unadulterated (sic) spirit of zeal to advance the glory of God.’ (Torah Temimah on Num 25 v7).

That, for me, is the clearest remit for and definition of zealotry and fanaticism that I know. It is the ultimate reversal of a wonderful hasidic adage “ Take care of your own soul and another person’s body, not of another person’s soul and your own body.” It encapsulates that terrifying absolute certainty that you know what God requires and that others do not. It declares with total conviction that human beings can stand in God’s place and hold sway over life and death, that we can execute, not in self-defence, not in the defence of the lives of others but to advance our own religious agenda and protect our own religious point of view. It seems to me to be a peculiarly male failing.

I do not have to spell out contemporary examples of those who appear to have seen in Pinchas and in similar scriptural authorities not simply justification but inspiration for becoming God and doing God’s supposed murderous will. In fact, part of my discomfort with Plaut may be explained by just how much the world has (apparently) changed over the last twenty-five years, how much more we are aware of the resurgence of fundamentalist zealotry, religious fanaticism and violent patriarchy.

Jews recall Brooklyn-born physician Baruch Goldstein who, apparently with the story of Esther in mind, went out just before Purim in 1994 and murdered twenty-nine Muslims in the Ibrahimi Mosque over the Cave of Machpelah in Hebron. And Yigal Amir who believed he was saving Israel by shooting Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin. Christians too have their fundamentalist zealots prepared to threaten violence, bomb and murder at abortion clinics in many parts of America. Islam has been hideously defaced by kidnappers and suicide bombers, for whom every conceivable act of inhumanity – and some that were even inconceivable before they were perpetrated – is justified by their religio-political goals and suitable Koranic texts.

Zealotry and fanaticism represent a facet of religion which disturbs me deeply. Pinchas is a terrifying role model, a dark character who seduces his fellow men from dark passages in our holy Torah.

So there we have it. A text, a sidrah against which I rebel from the very heart of my being. It is not that I cannot wrestle with it; it is not that I mind being challenged by it; and it is certainly not that I cannot find some things of merit, interest and religious quality within the narrative. But I rebel because it can be read and heard as having authority, as being worthy of reverence, as being God’s word. Which it is not. It can be taken up and used in ways which are absolutely antithetical to religion, to humanity and to the name of God. Too much of the commentary on this text, both ancient and modern, is self-justifying rather than self-critical, supporting blind obedience and justifying zealotry and fanaticism.

I stand up in honour of the Torah, follow it round the synagogue out of respect with my eyes and my posture. For this is a document touched by God. Like God, it does not offer a simple menu of impressive sound bites, homely truths and responsibility-absolving instructions. Rather, it challenges us even to the extent of asking us to struggle with texts which we ourselves can misunderstand, misuse or leave as hostages to fortune. It demands that we accept the fact that there are dark passages which are not God’s but ours, still ours – we men – even in Torah.

Bayfield, Tony. "Parashat Pinchas: 2009." Leo Baeck College Publications Weekly D'Var Torah. (Viewed on July 12, 2014). http://www.lbc.ac.uk/20090710914/Weekly-D-var-Torah/parashat-pinchas.html

Pinchas: A Covenant of Peace

By Rabbi Sylvia Rothschild

No biblical figure is so identified with zealotry as is Pinchas. He steps out in the closing verses of last week’s sidra, so outraged by the sight of a prince of Israel and a Midianite woman cavorting together that he acts immediately, not waiting for any legal process – he thrusts his spear into the couple as they lie together, and kills them both.

It is horrible to read, but more horrible still is God’s response. Pinchas is to receive a special reward – “Pinchas is the only one who zealously took up My cause among the Israelites and turned my anger away so that I did not consume the children of Israel in my jealousy. Therefore tell him that I have given him My covenant of peace” (Num 25:11-12)

Pinchas’ action ended an orgy of idolatry and promiscuity that was endangering the integrity of the people. But while the outcome was important, the method was terrible. And this rage which led him to act without any inhibition or process is not unique in bible. Remember the young Moses who murdered the Egyptian taskmaster? Or Elijah who slaughtered the priests of Baal?

These are events in our history which we cannot ignore, but neither can we celebrate. We have in our ancestry jealous rage and zealotry. So for example Elijah, having killed hundreds of idolatrous priests and demonstrating to his own satisfaction the falseness of their faith, finds that being zealous for God does not guarantee safety. Queen Jezebel is angered and Elijah had to run for his life to the wilderness. There he encounters many strange phenomena, but ultimately hears God not in the storms but in the voice of slender silence.

Moses’ act of killing was a little different – a young man who had only recently understood his connection to an enslaved people, he found their treatment unbearable, and when he found an Egyptian beating a Jew he looked around, saw no one so struck him and hid the body in the sands. Only the next day when he realised he had been seen, did he flee into the wilderness, there to meet God at the bush which burned but which was not consumed.

And Pinchas, whose act of violence grew from his anger against those who were mingling with the Midianite women and taking up their gods was rewarded by God with a ‘brit shalom’, a covenant of peace and the covenant of the everlasting priesthood.

Each of these men killed in anger – anger that God was not being given the proper respect, anger that God’s people were being abused. None of them repented their action, although Elijah and Moses were certainly depressed, anxious and fearful after the event. And God’s response seems too mild for our modern tastes.

Yet look at God’s responses a little more closely. Elijah is rewarded not by a triumphalist God but by the recognition of God in the voice of slender silence –the ‘still small voice’. That voice doesn’t praise him but challenges him – “What are you doing here, Elijah?” After all the drama Elijah has to come down from his conviction-fuelled orgy of violence and recognise in the cold light of day what he has done. Only when he leaves behind the histrionics does God become known to him – in that gentle sound of slender silence, and with a question that must throw him back to examine the more profound realities about himself and his own journey.

Moses too is not rewarded with great honour and dramatic encounter – his fleeing from the inevitable punishment is about survival and there is a tradition that Moses did not enter the promised land, not only because of what had happened at the waters of Meribah, but because that action brought to mind the striking of the Egyptian – Moses hadn’t learned to control his temper and his actions even after forty years of wandering in the wilderness.

Moses’ first encounter with God too was so gentle as to be almost missable. In the far edges of the wilderness alone with his father in law’s sheep this miserable young man saw a bush which burned but which wasn’t burned out. It is a story we know from childhood, but something we generally don’t recognise is that to notice such a phenomenon in the wilderness where bushes burned regularly, took time – Moses must have stood and watched patiently and carefully before realising there was something different about this fire. There is gentleness and the very antithesis of drama and spectacle, of the immediacy and energy of the zealot.

The reward for Pinchas is also not as it first seems. God says of him “hineni notein lo et breetee, shalom”. “Behold, I give him my covenant, peace”. The Hebrew is not in the construct form, this is not a covenant of peace but a requirement for Pinchas to relate to God with peace, and his method for so doing is to be the priesthood.

The words are written in the torah scroll with an interesting addition – the vav in the word ‘shalom’ has a break in it. The scribe is drawing our attention to the phrase – the violent man has not been given a covenant of peace but a covenant to be used towards peace – that peace is not yet complete or whole- hence the broken vav – it needs to be completed.

One of the main functions given to the priesthood is to recite the blessing of peace over the people, the blessing with which we end every service but which in bible is recited by priests as a conduit for the blessing from God.

Rabbi Shimon ben Halafta tells us “there is no vessel that holds a blessing save peace, as it says ‘the Eternal will bless the people with peace’” In other words, the eternal priesthood given to Pinchas forces him to speak peace, to be a vessel of peace so as to fulfil his priestly function. In effect, by giving Pinchas “breetee, shalom” God is constraining him and limiting his violence, replacing it with the obligation to promote peace. It is for Pinchas and his descendants to complete the peace of God’s covenant, and they cannot do so if they allow violence to speak.

Each of the three angry men – Moses, Pinchas, Elijah – are recognised as using their anger for the sake of God and the Jewish people, but at the same time each is gently shepherded into a more peaceful place. And this methodology is continued into the texts of the rabbinic tradition so that by Talmudic times self-righteous zeal is understood as dangerous and damaging and never to take root or be allowed to influence our thinking.

Times change, but people do not – there are still many who would act like Pinchas if they could: every group and every people has them. Their behaviours arise out of passionate belief and huge certainty in the rightness of those beliefs. Rational argument will never prevail against them, but gentle patient and persistent focusing on the goal of peace, our never forgetting the need for peace, must temper our zealots. Every tradition has its zealots and its texts of zealotry, but every tradition also has those who moderate and mitigate, who look for the longer game and the larger goal. We must keep asking ourselves, which group are we in today?

Rothschild, Sylvia. "Parashat Pinchas (2014)." Leo Baeck College Publications Weekly D'Var Torah." (Viewed on July 12, 2014). http://www.lbc.ac.uk/201407101866/Weekly-D-var-Torah/parashat-pinchas.html